Selling your Amazon FBA business is a major decision – and one key question is who should you sell to? The buyer you choose can shape not only your payout, but also the sale process and what happens to your brand after the deal. The three common buyer types are aggregators, private buyers, and investors (such as private equity firms). Each comes with different motivations, deal structures, pros, and cons. In this guide, we’ll break down what each type of buyer looks like, the advantages and disadvantages of selling to them, how their deal offers tend to be structured, and the factors you should consider to choose the best fit for your Amazon FBA exit. The tone here is neutral and seller-centric – the goal is to help you make a strategic decision that aligns with your priorities as a seller.

Aggregators: The Amazon FBA Roll-Up Companies

What is an Aggregator? Aggregators (also known as FBA roll-up firms) are specialized companies that acquire and consolidate Amazon FBA brands. Over the past few years, many aggregators (like Thrasio, Perch, and others) have raised significant capital to buy up successful FBA businesses and build a portfolio of brands. They typically have expert teams in place – Amazon specialists in areas like supply chain, PPC advertising, and listing optimization – and a playbook for scaling the brands they purchase. Aggregators usually target businesses of a certain size (often mid-6 figures up to 7 or 8 figures in annual revenue) that fit their criteria (profitable, growing, good product reviews, etc.). If your FBA business is relatively large and stable, it may attract attention from aggregators.

Pros of Selling to an Aggregator:

- Quick, Streamlined Sale: Aggregators are professional buyers who value speed. They often move fast – it’s not uncommon for an aggregator to close a deal in as little as 30-60 days once an offer is accepted. The process is fairly streamlined; they’ve done many acquisitions and have standard procedures for due diligence and transferring Amazon accounts. This can mean less time “in limbo” for you compared to a lengthy sale process with other buyers.

- Amazon Expertise for a Smooth Transition: Because aggregators focus on Amazon businesses, they understand the FBA model inside-out. They have dedicated transition teams to take over operations. For a seller, this means the handover is usually smooth and doesn’t require you to spend months teaching a newcomer all the Amazon quirks. You hand over the keys, and their team knows how to run and grow the brand.

- Potentially Higher Total Payout: Aggregators often offer competitive valuations – sometimes higher headline multiples of your profit than an individual buyer might pay. Importantly, their deals frequently include earn-outs or performance-based payments that let you participate in the future success of the brand. If the aggregator grows your brand after acquisition (which is their goal), you could earn additional payouts. In other words, you might get a second bite at the apple if the business performs well post-sale. This structure can maximize the total money you receive (more on deal structures later).

- No Need to Stay On: Generally, aggregators want to take full control of the business. They don’t expect (or want) the original owner to stick around long-term. For you, that means a clean exit – aside from a short transition/training period of a few weeks or months, you won’t be required to run the business after selling. This is ideal if you’re eager to move on to your next project or take a break, without strings attached.

Cons of Selling to an Aggregator:

- Structured Deals (Earn-Outs and Holdbacks): The flip side of those generous earn-out structures is risk. Aggregator offers often come with deferred payments – for example, you might get 70%-80% upfront and the rest paid later contingent on the business hitting certain targets (or simply staying steady) for 6-12 months. If the brand underperforms after you hand it over (or if the buyer’s management isn’t up to par), you could end up with a lower total price than expected. In short, not all the money is guaranteed at closing. This structure protects the buyer and gives you incentive to ensure a smooth transition, but it means you carry some post-sale risk.

- Hard-Nosed Negotiations: Aggregators are experienced negotiators whose core business is acquiring companies at the right price. They typically have a very data-driven valuation model (based on your TTM profit, growth trends, etc.) and may not be very flexible on price. In private sales without other bidders, some savvy aggregators will try to acquire businesses for a bargain. If you’re not well-prepared or don’t have multiple offers, you might sell for less than the business is worth. (Aggregators have an edge because they know the market well – they won’t overpay, and they might spot mistakes in your financials that they won’t rush to point out unless you do!)

- Loss of Brand Autonomy: When an aggregator takes over, your brand becomes one of many in their portfolio. Their goal is to scale it and integrate it with their operations. That can mean changes to branding, product lines, or strategy that you might not have done yourself. If you’re emotionally attached to your brand’s vision or way of working, it can be tough to see it absorbed into a larger machine. The brand’s legacy may shift as the aggregator might streamline the business – for example, discontinuing products that don’t meet their profitability targets or even folding your brand into another umbrella brand. In short, you relinquish control, and the aggregator will do whatever they think is best for growth and ROI.

- Not Ideal for Very Small Businesses: Most big FBA aggregators have minimum criteria (often a few hundred thousand in annual profit or at least $1M+ in revenue). If your business is on the smaller side, an aggregator might not be interested at all. This isn’t a “con” per se – it just means for many smaller Amazon sellers, selling to an aggregator isn’t a realistic option until they grow more.

Private Buyers: Individuals or Small Acquirers

Who is a Private Buyer? A private buyer means an individual (or a small company) who acquires your Amazon FBA business directly, rather than an institution or fund. This could be an entrepreneur looking to jump into the FBA space without starting from scratch, a former Amazon seller wanting a new project, or even another Amazon seller/operator who wants to add your brand to their own portfolio (without being a large formal aggregator). Private buyers encompass a range – from first-time buyers to mom-and-pop investors, or even competitor brands in your niche that see value in taking over your operation. If your business is smaller or mid-sized, private buyers will likely be the most common suitors, since they’re often looking at deals under the multimillion-dollar range.

Pros of Selling to a Private Buyer:

- Simplicity of Deal: Deals with individual buyers are often more straightforward. Many private buyers will offer a mostly cash or financed deal at closing, without complicated earn-out provisions. For example, an individual might get an SBA loan (in the U.S.) or use their savings/investors to pay you the full price upfront. In some cases they might ask for a short seller financing period (e.g. pay 80-90% now and the rest over 6-12 months), but it tends to be simpler than the multi-year profit-share earnouts that aggregators use. This can be attractive if you prefer a clean break and as much cash upfront as possible. Fewer contingent payments mean less worry about what happens after the sale.

- Potential for a Personalized Touch: When selling to an individual, especially someone who will personally run the business, the negotiation can feel more personal and flexible. You’re dealing directly with a human who may be excited about your brand. If maintaining your brand’s ethos or legacy is important, you might prefer handing it over to someone who shares that passion. A private buyer who loves your niche or product may continue the business in the same spirit. (For example, an ex-military entrepreneur buying a tactical gear FBA brand might be genuinely invested in the product line’s success and identity.) This isn’t guaranteed, but one-on-one sales allow you to gauge the buyer’s vision for the brand and maybe find a “good home” for it.

- Broader Pool for Small Businesses: If your Amazon business is below the size threshold that big investors seek, private buyers are likely your main option (aside from holding the business until it grows more). The good news is there are plenty of individuals and small operators looking to buy FBA businesses as an investment or a job-replacement income. This means you can sell even a smaller FBA business via marketplaces or networking, whereas large aggregators or PE firms might ignore it. Private buyers often look for deals in the low six-figure to low seven-figure range, which covers many Amazon sellers.

- Negotiation Flexibility: Unlike a large firm with a rigid model, an individual buyer may be more flexible in negotiations. They might be willing to get creative to make the deal work – for instance, structuring payments around an SBA loan schedule, or including perks like a consulting agreement for you if you’re open to it. If something in the deal is important to you (say, you want a longer transition period or you want to keep a minor revenue stream), an individual is someone you can talk it out with, rather than face a “take it or leave it” term sheet. This person-to-person flexibility can result in a win-win structure tailored to both parties’ needs.

Cons of Selling to a Private Buyer:

- Financing Risks and Slower Process: Many private buyers rely on financing (bank loans, SBA loans, or investors backing them) to afford the purchase. This means the sale can take longer and is less certain to close. For example, an SBA loan approval can take a couple of months and if the loan falls through at the last minute, the deal might collapse. There are also more steps where things can hit a snag – appraisals, underwriting, etc. compared to an all-cash aggregator. As the seller, you need patience and should vet the buyer’s financial capability. There’s a chance of wasted time if their funding doesn’t come together. In short, closing with a private buyer may not be as lightning-fast as an aggregator’s timeline.

- Less Experience & Resources: An individual buyer is likely not as experienced in acquisitions as an aggregator or PE firm (unless they’ve bought businesses before). They might be buying their first Amazon business. This can lead to hiccups in due diligence and transfer. For instance, a newbie buyer might ask endless basic questions, get cold feet, or be unfamiliar with Amazon’s transfer process. You, as the seller, might need to hand-hold the buyer more through closing and post-sale. Additionally, a private buyer doesn’t come with a built-in management team. If you’ve promised an earn-out or seller financing, you’re betting on this individual to run the business well enough to pay you — which can be risky if they lack Amazon experience.

- Lower Valuations (Often): Private buyers typically have a tighter budget and return targets, so they may not pay as high a multiple as an institutional buyer would for the same business. They might be looking for a “good deal” or have a limit based on their loan approval. In general, smaller buyers pay smaller multiples (e.g. maybe 2.5-3.5× annual profit for a smaller FBA business) whereas a larger aggregator might pay 4-5× for a bigger, more stable brand. Every deal varies, but don’t be surprised if individual buyers come in with more conservative offers. If maximizing price is your top priority, one lone private buyer bidding might not get you there – you may need to seek multiple interested parties to bid up the price.

- You Might Need to Assist More Post-Sale: With a private buyer, especially an owner-operator type, they often appreciate if the seller stays on for a while to mentor or consult. Of course, once you’re paid and the business is transferred, you don’t have to run it – but out of goodwill (or contractual agreement), you may end up spending significant time after the sale helping the new owner get up to speed. This can be in the form of a few weeks of intensive training or an open line for questions for several months. While this is usually manageable, it’s a bigger commitment than selling to a well-oiled aggregator that needs minimal help. Be prepared to allocate time for a thorough knowledge transfer so the buyer feels confident taking over.

Investors (Private Equity and Other Investment Firms)

Who is an Investor Buyer? In this context, “investor” refers to larger financial buyers like private equity (PE) firms, investment funds, or “incubators” that invest in businesses. These are companies or funds that might buy a controlling stake in your Amazon FBA business as an investment, rather than to fold it into an existing portfolio of Amazon brands (like an aggregator would). Private equity firms often look for businesses with substantial profits (often higher-end FBA businesses, e.g. $2M+ EBITDA), and their model is usually to buy, grow with the existing team or management, and sell later at a profit. In some cases, an “investor” could also be a strategic buyer – for instance, a larger consumer goods company or a family office that wants to acquire your brand for strategic reasons. The common thread is that these buyers have significant capital and a longer-term investment horizon. They might not have deep Amazon expertise themselves, but they see your business as a valuable asset to invest in.

Pros of Selling to an Investor:

- Opportunity to Retain Equity (Second Bite at the Apple): Unlike aggregators or most individual buyers, many private equity investors prefer that you keep a stake in the business post-acquisition. For example, a PE firm might buy 70-80% of your company, and have you retain the remaining 20-30%. This retained equity is often called “rollover equity.” The benefit? When the investor later sells the company (say in 2-3 years, perhaps to an even bigger fund or strategic buyer), you get a second payday based on that remaining equity. This can be very lucrative if the business grows significantly under their stewardship – you’ve already taken some chips off the table by selling most of it, but you still ride the upside on the portion you kept. For a seller who believes there’s big future potential and doesn’t mind staying involved, this scenario offers both liquidity now and a share of future growth.

- High Upfront Valuation: Investment firms often pay well for quality businesses. If your FBA brand is large and profitable, a private equity buyer might offer a strong multiple (often in the range of 4× to 6× annual profit, depending on growth and risk factors) paid mostly in cash upfront. In fact, in head-to-head comparisons, the cash you get at closing from a PE firm can rival or exceed what an aggregator would pay upfront. They tend to structure deals with big upfront checks plus the rollover equity instead of earn-outs. So if your goal is maximizing immediate cash proceeds (and your business is attractive enough to draw PE interest), this route can deliver a sizable sum.

- Growth Capital and Resources: A good investor will bring capital for growth and operational resources. They might invest additional money into new product lines, expanding to new marketplaces, or marketing campaigns to significantly scale the brand. Some PE firms will also provide experienced executives or advisors to help run the business (especially if they want you to eventually step back). If you care about seeing your brand become a much larger player, selling to an investor who plans to grow and “flip” the business in a few years can be appealing. They aren’t just maintaining status quo – they typically want to at least double the business size before exit. This means your brand could reach new heights under their ownership, which can be gratifying if you still hold a stake.

- Sophisticated, Professional Process: Generally, private equity firms and similar investors are professional deal-makers. The process will be thorough, but they know what they’re doing. They’ll conduct comprehensive due diligence and legal processes, which can actually be reassuring – you’re less likely to have random last-minute surprises or the deal falling apart for emotional reasons. Everything is more business-like. Negotiations will be data-driven and contract terms clearly laid out. While this can feel intense, it also means once an agreement is signed, these firms have reputations to maintain and are likely to follow through diligently. For a seller, that can provide confidence that the deal will complete (assuming your business checks out in diligence).

Cons of Selling to an Investor:

- You May Need to Stay Involved: If your plan was to fully exit and walk away, selling to a private equity firm might not be the best fit. Investors usually want the founder or management to continue running the business (at least for a while) because they see value in the existing team’s knowledge. In many PE deals, you might be required to stay on as CEO or consultant for a year or more, or until they find a suitable management replacement. Even if not required, it’s often implied – after all, you still own a piece via rollover equity, so they expect you to remain invested (both figuratively and literally) in the business’s success until the next liquidity event. This can be a drawback if you’re feeling “done” with the business or burned out. With an aggregator or private buyer, you can usually cut ties quickly; with a PE investor, you’re signing up for a partnership for a period of time.

- Longer, More Complex Sale Process: Out of all the buyer types, a private equity or institutional investor deal is typically the most complex and time-consuming to close. There will be extensive due diligence (they will comb through your financials, operations, supply chain, legal compliance, etc.). Lawyers will draft detailed contracts (often longer and more detailed than a standard asset sale agreement from an aggregator). Negotiations may go through multiple rounds – the investor might have an investment committee that needs to approve, etc. It’s not unusual for a PE deal to take several months from LOI to closing. If you value speed or are not prepared for a rigorous process, this can be a hurdle. The deal can also be expensive on your end – you may need to hire your own attorney or accountant to help, given the complexity.

- Higher Bar to Qualify: As mentioned, not every FBA business will interest a PE firm or large investor. They typically seek larger, well-established brands, often those with opportunities to expand outside Amazon or with strong differentiation. If your business is smaller or purely Amazon-focused without other channels, some investors will pass (unless they specialize in FBA roll-ups, which blurs the line between investor and aggregator). In essence, the pool of true “investor” buyers is smaller and more exclusive. You might spend time courting a PE firm only to be told your business is too small or doesn’t meet their criteria. This path tends to be viable mostly for top-tier FBA businesses in terms of size and profitability.

- Shared Control and Vision: Bringing on an investor means you no longer have the final say in your business’s direction. Even if you retain 20% and continue as an operator, the majority owner (the investor) will ultimately call the big shots. They might decide to pursue strategies you’re not 100% on board with (e.g. aggressive expansion that could be risky, or even preparing the business for a later sale in a way that you wouldn’t have). You have to be comfortable with giving up control and possibly adapting to a more corporate management style. Board meetings, performance targets, and increased reporting are common under PE ownership. For some entrepreneurs, this shift is frustrating – you go from being your own boss to answering to new owners.

Comparing Deal Structures and Negotiations Across Buyer Types

One of the biggest differences between aggregators, private buyers, and investors is how they structure the deal and negotiate the terms. Understanding what a typical offer looks like from each can help you prepare and decide which aligns with your goals. Here are some example deal structures and negotiation dynamics you might encounter:

- Aggregator Offer Example: An aggregator might propose a price based on, say, a 4× multiple of your annual Seller Discretionary Earnings (SDE). However, you might not get it all at once. A common aggregator deal could be 70% upfront cash, and 30% as an earn-out or “stability payment” over the next 12 months. For instance, if they value your business at $1,000,000, they might pay $700,000 at closing, then hold $300,000 contingent on the business hitting certain revenue/profit targets or at least not declining in the year after sale. They may also include an earn-out tied to growth – e.g. an extra bonus if the brand’s net profit exceeds its pre-sale level. Negotiation focus: You would negotiate the targets for those deferred payments, the time frame, and any minimum guarantees. Aggregators often have a standard formula, but there is room to discuss what metrics define a “stable” business or growth for earn-out purposes. Because aggregators do many deals, their purchase agreements are usually standardized – you can expect a relatively seller-friendly process on things like escrow, asset transfer, etc., but not a lot of deviation on price structure. Non-compete clauses will definitely be included (preventing you from starting a competing Amazon brand for a couple of years). Overall, aggregator negotiations are businesslike: they typically won’t nickel-and-dime small issues, but they also won’t overpay their set valuation. It’s often a relatively quick negotiation focused on the multiple and performance terms. Be prepared to justify your business’s value with solid numbers – they’ll likely have seen it all and will base their offer on data.

- Private Buyer Offer Example: A private buyer’s deal might be simpler in structure. For example, an individual buyer could offer a fixed price of $500,000 all-cash for your business, funded by a bank loan. Or, if not all cash, they might propose something like 90% at closing and a 10% seller note (a promissory note) to be paid over one year (perhaps with interest). In some cases – especially if the buyer is another small e-commerce business – they might structure an asset purchase where they pay for your inventory separately at cost and then pay a multiple on your profit for the goodwill. Negotiation focus: With private buyers, negotiation often revolves around the total price and financing contingencies. They may be more price-sensitive; expect counteroffers and justification (“Your TTM profit is X, I think a 3× multiple is fair because of Y…”). You might have to negotiate the terms of any seller financing (interest rate, collateral) or an escrow holdback for a few months in case of any unexpected liabilities. Also, expect to agree on a training period or transition assistance explicitly: e.g. “Seller will provide up to 40 hours of training/consulting in the first 3 months.” Private buyers might request that as part of the deal. The process with an individual can be a bit more fluid – there may be more back-and-forth on small details (what happens with your LLC, the transfer of vendor relationships, etc.) since they don’t have a template for everything. Patience and clear communication are key. Keep in mind, if their offer is contingent on a loan, the negotiation might also involve satisfying the bank’s requirements (for instance, the bank might require that the business appraises at the sale price or that you sign a non-compete). You and the buyer need to cooperate to clear those hurdles.

- Investor (Private Equity) Offer Example: An investor might structure a deal in two parts: a majority stake purchase plus an equity rollover. For example, a private equity firm could value your FBA business at $10 million (perhaps a ~5× EBITDA multiple if your annual EBITDA is around $2M). They might offer $8 million to buy 80% now, and roll the remaining 20% equity for you to keep. That $8M could largely be cash at closing, with possibly a small portion deferred or held in escrow for adjustments (investors often prefer clean entry, but they might hold back, say, 5-10% for a year to cover any unforeseen liabilities). Negotiation focus: These negotiations are more complex and cover a lot of ground. Price and equity split are major points – you’ll negotiate how much of the business you’re selling now and at what valuation. If you retain equity, you’ll also negotiate the terms around that: will you have any say in the business post-sale? How will a future sale be decided? There will be discussions about your role going forward (Are you staying as CEO? For how long and on what compensation? Or perhaps transitioning out after a period?). The investor will likely require detailed warranties and representations about your business in the contract – expect negotiation on legal points like indemnities (i.e. what happens if something goes wrong post-sale that originated before sale). It’s advisable to have a lawyer for this stage. Additionally, if the investor is not 100% familiar with Amazon FBA nuances, part of your negotiation (or at least, discussion) might be educating them on things like Amazon’s rules, the need for working capital for inventory, etc., to ensure they understand the business they’re buying. Private equity deals might also involve an earn-out or performance bonus similar to aggregators, but often they substitute that with the equity rollover (so you only gain if the whole business’s value increases later). Prepare for a longer negotiation timeline with multiple drafts of documents. It’s a more formal M&A process, but the upside is a potentially higher payout and a partner to help grow the business.

Who holds the leverage in negotiations? It often comes down to the market demand for your business and your own willingness to walk away. Aggregators typically have a lot of options (they see many deals), so they may not bend much unless your business is a real prize or you have competing offers. Private buyers might feel more urgency (especially if they’ve been searching for a good business for a while), but they also might have budget limits. With investors, they’ll be very thorough – if they’ve decided your business fits their thesis, they’ll negotiate hard but fair; if you have other options (like an aggregator offer on the table), letting them know can sometimes encourage a better offer from them. In all cases, having multiple interested parties puts you in the best position. If you can create a bit of competition – say, engage with a few aggregators and private buyers via a marketplace or broker – you’re more likely to get strong offers and terms, rather than accepting the first thing that comes along.

Factors for Sellers to Consider When Choosing a Buyer

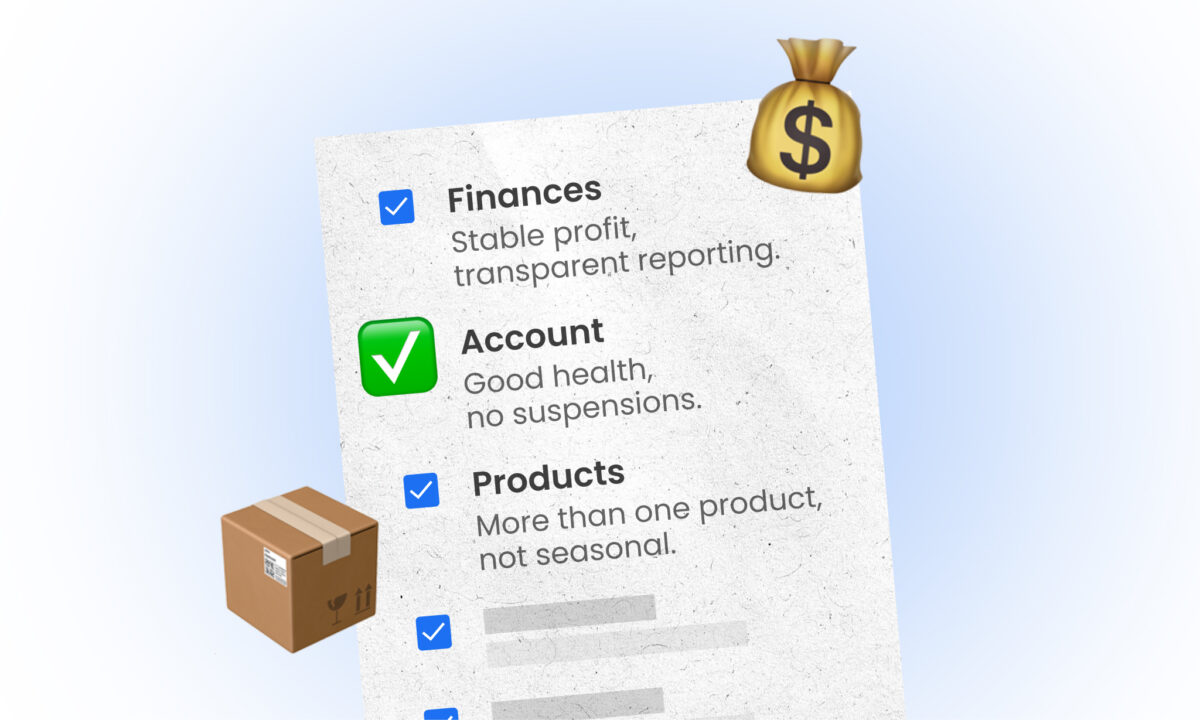

Every seller’s situation and goals are unique. When deciding between selling to an aggregator, a private buyer, or an investor, consider the following factors to determine which buyer type aligns best with your priorities:

- Valuation & Price: Different buyers may use different valuation methods and offer amounts. Aggregators and private buyers often value your business based on a multiple of SDE (Seller’s Discretionary Earnings) or EBITDA, derived from the past 12 months of financial performance. An aggregator might have a fairly standard range (adjusted for growth or risk factors) and may not drastically overbid beyond market multiples. A private individual might base their offer on what they need for a certain return or what their financing will cover – sometimes resulting in a slightly lower multiple. Investors (PE firms) might be willing to pay a premium if your business is large and strategic enough, because they see the potential to sell it later at an even higher multiple. Ask yourself: Is getting the absolute highest price your top goal, or are you comfortable with a fair price that comes with other benefits (like quick close or low risk)? If maximizing price is king, you may want to cast a wide net (multiple buyers or a broker-mediated auction) and see if a PE or strategic investor enters the fray. If you get an offer, examine not just the headline price, but how it’s calculated and paid out (all cash vs. earn-out). Sometimes a slightly lower all-cash offer can be “worth” more to you than a higher number that’s mostly deferred or contingent.

- Payment Structure (Cash vs. Earn-Out vs. Equity): The structure of the deal can be just as important as the price. Do you need most of the money upfront for your goals? If you’re counting on the sale to, say, buy a house or fund a new venture immediately, an offer with 100% (or high percentage) cash at close is more valuable to you. Private buyers and some investors might fit this bill better than aggregators, since aggregators love structured payouts. On the other hand, if you don’t mind waiting and are optimistic about the business’s future, an earn-out or equity rollover could significantly increase your total proceeds. Aggregators commonly use earn-outs and stability payments – great if the business continues doing well (or if you believe the aggregator will enhance it), but remember you’re handing over control, so you’re trusting them to not drop the ball. Investors often use equity rollovers – this can yield a big second payout, but only if in a few years the market and the business cooperate. Think about your risk tolerance and trust: Are you comfortable betting a portion of your sale on the business’s post-sale performance (which you won’t fully control)? Or would you rather take a slightly lower, guaranteed sum and walk away? There’s no right answer, just what suits your needs and peace of mind.

- Speed and Certainty of Close: How quickly do you want (or need) the deal to happen? The timeline to close can vary a lot:

- Aggregators are generally the fastest option – they often can present an LOI within days of contact and close within a month or two, because they have dedicated teams and capital ready to deploy. If you value a quick, certain exit, aggregators excel here (as long as your business passes their due diligence).

- Private buyers can range from fairly quick to slow, largely depending on financing. All-cash individual buyers can close fast, but those relying on loans may need ~60-90 days or more. Plus, there’s always a small chance the loan doesn’t get approved or the buyer gets cold feet, which introduces uncertainty.

- Investors (PE firms) usually take the longest. Their diligence is deeper and internal approval processes more involved. It’s not uncommon for a PE deal to take 3-6 months from start to finish. They also might be evaluating other deals parallelly, so things could drag a bit.

- Aggregators are generally the fastest option – they often can present an LOI within days of contact and close within a month or two, because they have dedicated teams and capital ready to deploy. If you value a quick, certain exit, aggregators excel here (as long as your business passes their due diligence).

- Consider your own situation: Is there urgency? (e.g., personal reasons like health, burnout, another opportunity calling you, or simply wanting to capitalize on a hot market quickly.) If so, lean toward the buyer who can close efficiently. Also assess the reliability: an aggregator with a solid track record or an established PE fund is unlikely to flake on a signed LOI, whereas an inexperienced private buyer might. The last thing you want is to waste months and have a deal fall through. So, if you pursue a private buyer, vet their financial capacity early (proof of funds or pre-approved financing) to gauge certainty.

- Your Desired Level of Post-Sale Involvement: Think about what role (if any) you want after selling. Do you wish to completely hand over the reins and exit the business immediately? Or are you open to (or even interested in) staying involved in some capacity? Your answer will steer you:

- For a clean break, aggregators or many individual buyers are suitable. Aggregators will require only a brief transition period (you train their team and then you’re done). Private buyers, after a handover period, generally won’t expect you to keep working in the business either (they bought it to run it themselves). In contrast, most investors (PE) will expect you to stick around to continue leading or at least guiding the business, since they usually invest in the team as well as the company. Selling to a PE firm is more like taking on a business partner than truly exiting – at least until that second sale happens.

- If you still enjoy the business and just want some liquidity or help scaling, a partial sale to an investor could be ideal. You’d get to take some cash out, retain equity, and work with the new owners to grow it bigger (with more resources at your disposal). That can be exciting for the right founder. Alternatively, if you want to step back from day-to-day operations but still leverage your expertise, some aggregators or buyers might offer a consulting arrangement post-sale (usually short-term).

- Be realistic and clear with yourself: once you sell, even if you stay involved, the dynamic changes – you’ll be reporting to someone (the new owner or majority shareholder). If that doesn’t sit well with you, better to aim for an outright exit. On the flip side, if you have more to contribute to the brand’s story, picking a buyer who welcomes that (likely an investor) will be important.

- For a clean break, aggregators or many individual buyers are suitable. Aggregators will require only a brief transition period (you train their team and then you’re done). Private buyers, after a handover period, generally won’t expect you to keep working in the business either (they bought it to run it themselves). In contrast, most investors (PE) will expect you to stick around to continue leading or at least guiding the business, since they usually invest in the team as well as the company. Selling to a PE firm is more like taking on a business partner than truly exiting – at least until that second sale happens.

- Future of the Brand & Legacy: Many Amazon sellers care deeply about the brand they’ve built – it can feel like your “baby.” If the future legacy of the brand matters to you, consider who would manage it the way you’d approve of:

- An aggregator will treat your brand as an asset to grow and integrate. They might infuse it with capital, launch new products, and expand it globally – which could turn your small brand into a much bigger name. That’s a positive legacy in terms of scale. However, aggregators may also rebrand, reposition, or cost-cut. The brand could lose some uniqueness as it becomes one of many under a corporation. Also, if down the line the brand underperforms, an aggregator might even discontinue it (worst-case). So, if preserving the brand’s mission or quality is paramount, grill potential aggregators about their plans for your brand.

- A private buyer might keep things more consistent, at least initially. If they’re an owner-operator, they have a personal stake in seeing the brand thrive similarly to how you did. They might be more cautious about drastic changes. If they love the product and niche, they’ll likely nurture the brand identity. Of course, a lot depends on the individual – a buyer could also pivot the brand in ways you wouldn’t, but generally, an individual taking over a single business will focus on continuity to keep the cash flow.

- An investor/PE may have big plans – possibly expanding the brand beyond Amazon (into retail or other channels) or even merging it with another company. This could elevate the brand’s presence or transform it significantly. PE firms ultimately plan to sell the business again, possibly to a large corporation. So your brand could end up under a much larger corporate umbrella in a few years. If you dream of your brand becoming a household name, a savvy investor could help make that happen. But if you worry a larger owner might dilute the brand’s values, that’s something to weigh.

- An aggregator will treat your brand as an asset to grow and integrate. They might infuse it with capital, launch new products, and expand it globally – which could turn your small brand into a much bigger name. That’s a positive legacy in terms of scale. However, aggregators may also rebrand, reposition, or cost-cut. The brand could lose some uniqueness as it becomes one of many under a corporation. Also, if down the line the brand underperforms, an aggregator might even discontinue it (worst-case). So, if preserving the brand’s mission or quality is paramount, grill potential aggregators about their plans for your brand.

- In summary, decide how important the post-sale stewardship of the brand is to you. Once you’ve sold, you won’t control its destiny, but you can choose an owner whose vision aligns with yours. In your discussions, you can ask buyers “What do you see for the brand 1-2 years after acquisition?” Their answers can be telling. Some sellers ultimately choose a slightly lower offer from a buyer they trust to honor their brand, over a higher offer from someone they have reservations about – it’s a personal decision.

- Deal Complexity & Costs: Consider the complexity of the transaction and how much hassle you’re willing to go through. An aggregator deal is usually relatively standardized (asset purchase agreement, etc.) and the aggregator often has a clear checklist for you, making it easier to navigate. With a private buyer, if you’re not using a broker or platform, you might have to manage more of the process (think: coordinating escrow, drafting the sale contract, etc.). If the buyer is new, you may also need to guide the logistics (for example, how to transfer the Amazon Seller Account safely, how to handle inventory in Amazon’s FBA warehouses, etc.). This can be managed, but it’s extra work on your plate during the sale. Investor deals, as noted, are the most complex legally – be ready for a heavier paperwork burden and to possibly hire professional help (transaction attorney, accountant) which can eat into your time and some money. Evaluate your comfort and resources: If you’re not in a rush, you can handle a complex process. If your attention is needed elsewhere or you just want a simple handover, that might push you toward a buyer who offers a turnkey process (some aggregators even cover closing costs or have in-house legal, easing the burden on you).

- Business Size and Market Conditions: Finally, be realistic about your business’s size and the current market climate in the FBA acquisition space. In booming times, aggregators might be more aggressive and private buyers plentiful; in slower times, some buyer types might tighten their criteria. If your business is on the smaller side (for example, <$200K annual profit), a private buyer is likely your primary pool – an investor firm probably won’t consider it, and many big aggregators also won’t. Conversely, if your business is quite large (say $5M+ annual profit), you might be one of the rarer targets that attract all three types – aggregators, PE, and even strategic buyers could all bid. The larger and more profitable the business, the more options you have (and you may even consider hiring a broker or investment bank to run a formal selling process to maximize value). For a mid-sized business, aggregators and experienced individuals (or small funds) will be your likely buyers. Know where your business stands so you spend time with the right category of buyers. And keep an eye on market trends: for instance, in recent years Amazon aggregators had a phase of rapid growth and intense buying, followed by some pullback and more selective acquisitions. Private equity interest in FBA brands has also evolved. Market conditions can affect how much each type might pay and how eager they are. Doing a bit of research or speaking with an advisor about the current “seller’s market” vs “buyer’s market” sentiment can inform your strategy (e.g., if aggregators are retrenching, maybe a private buyer route becomes more appealing at that time, or vice versa).

Conclusion: Making the Right Choice for Your Amazon FBA Exit

When deciding whether to sell your Amazon FBA business to an aggregator, a private buyer, or an investor, the “right” choice ultimately depends on your personal goals, the specifics of your business, and the trade-offs you’re willing to accept. There is no one-size-fits-all answer. Take the time to reflect on questions like:

- Am I aiming for the highest possible price, or do I prioritize a fast and certain sale?

- Do I want to be completely done with the business, or do I see myself still involved in its future growth?

- How important is it to me who takes over and how they run the brand I built?

- Does the potential buyer have the means and experience to actually close the deal and successfully run the business afterward?

By considering the pros and cons of each buyer type, you can match those to your priorities. For example, if you want a quick exit and a smooth handover with minimal future involvement, an aggregator might be your best fit. If you have a smaller business or value a personal touch, a private buyer could be ideal – just be diligent about their credentials. If you have a larger business and still have the drive to scale it further (but with some cash in your pocket now), an investor/PE firm partnership might give you both immediate reward and future upside.

Whichever route you choose, prepare your business well for sale (clean financials, solid performance, documentation) and do your homework on the buyer. A well-prepared seller with a clear goal will be able to negotiate confidently and smartly. In the end, the best deal is the one that not only maximizes value for you but also feels right in terms of the next chapter for you and your brand.

Good luck with your Amazon FBA exit, and stay strategic – this is your opportunity to reap the rewards of all the hard work you’ve put into your business! Enjoy the process, stay informed, and make the choice that serves you best as a seller. Your successful exit is on the horizon.